Building scalable software means that you are prepared to accommodate growth. There are basically 2 things you need to consider as your data grows:

- Will requests be handled at a faster rate than they come in?

- Will my hardware be able to store all the data?

Obviously, you will need more infrastructure as you grow. You’ll need more machines. You’ll probably also need/want to introduce additional applications to help lighten the load, like cache servers, load balancers, …

Introduction

Imagine a self-sufficient village of 1000 inhabitants that grows to a population of a million. While the initial power supply network was state of the art, it was not quite fit for this magnitude. In order to service more residents, your power plant will need to both produce more power.

Horizontal & vertical

Vertical scaling means that you increase your overall capacity by increasing the capacity of its machines. E.g.: if you’re running out of disk space, you could add more hard disks to your database server.

Horizontal scaling means adding more machines to your setup.

In our village-analogy, scaling vertically would be adding a nuclear reactor to your power plant, to increase the amount of power that can be generated. Scaling horizontally would mean building a second power plant. Vertical scaling is the easiest: the rest of the existing infrastructure still works. Scaling horizontally means you’ll need additional power circuits from and to the new plant, new software to keep track of the flow of energy between both plants, …

In computer hardware, scaling horizontally (a cluster of lower tier machines) is usually cheaper compared to scaling vertically (one supercomputer). It also provides failover: if one machine dies, the others can take over. However, horizontal scaling is often harder from a software point of view, because data is now distributed over multiple machines.

Read-/write-heavy

Read-heavy applications are usually easier to scale. Being read-heavy means there are plenty more requests that only need to fetch (and output) data, compared to those that store data.

Read-heavy applications are mostly about being able to service requests. What you need here is enough machines to handle the load: enough application servers to do the computing and/or enough database slaves to read from (more on both later.)

Write-heavy applications will need even more careful planning. Not only will they likely have the read-problems as well, you’ll also need to be able to store the data somewhere. If there’s lots of it & continuously growing, it might outgrow your machine.

Application & storage servers

Applications servers are the ones hosting your PHP, Python, … code. Those aren’t really that hard to scale: code doesn’t typically change based on user-input (that stuff is in the database). If you run your code on machine A or machine B, it will do the exact same thing.

Scaling your code is just as easy as adding it to more machines. Put your code on 10 machines with a load balancer in front of them to evenly distribute the requests to all 10 machines, and you’re now able to handle 10x as much traffic. The important thing in you application is that it’s as effective as possible, and actually able to handle lots of requests.

The issues on storage are completely different. Well, the read-issues are comparable (have enough copies on enough machines) - the write issues require hard thinking about how, exactly, you’ll store your data.

Application

CPU

An application consists of a lot of “instructions” (= your code). If a request comes in, your code will start doing a bunch of things (= processing) in order to finally respond with the appropriate output.

The amount of requests your server is able to respond to is limited by the capacity of the hardware, so you’ll want to keep “what the machine has to do to service the request” as simple as possible, even if the machine is capable of doing a lot. This way, it can handle more requests.

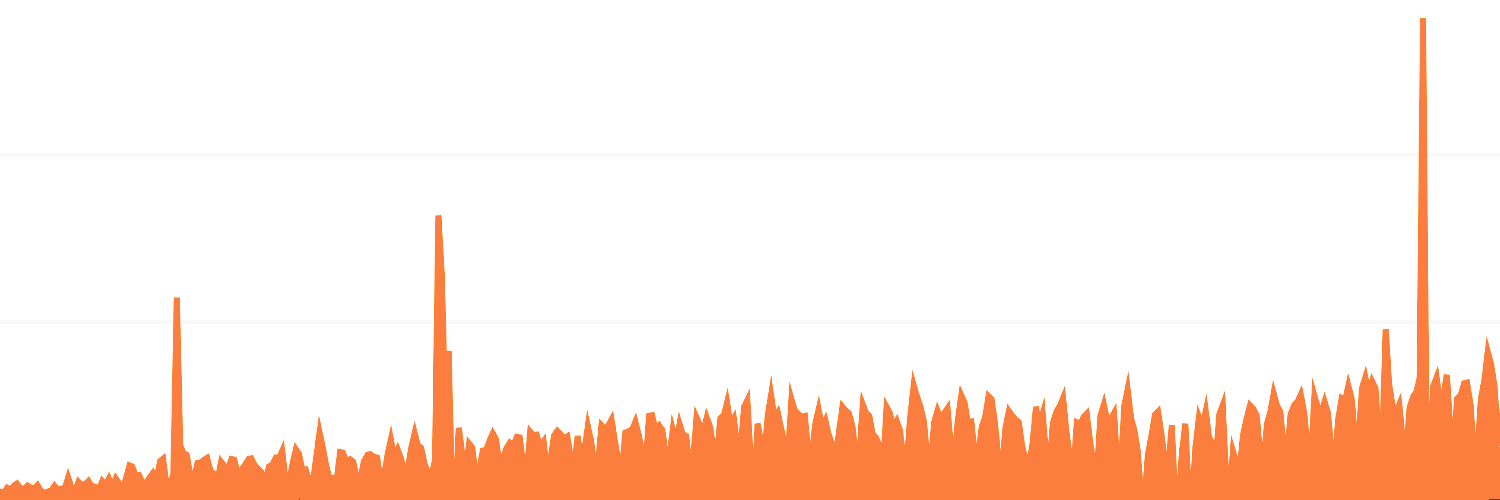

The problem with CPU-intensive applications is that if something takes an increasingly long time to compute, response time will be delayed, the amount of requests you’re able to handle will lower & eventually you won’t be able to service all requests.

If your CPU-intensive work is not critical for the response (you don’t need to immediately display the result of it), you should consider deferring the work to a job queue, to be scheduled for later execution.

Memory

The problem with memory-intensive applications is twofold:

- Your processor may be idling until it can access occupied memory, thus delaying your response time (same problem as with CPU-intensive applications)

- You may be trying to fit more into the memory than is possible, and the request will fail.

Always try to limit your unknowns: if you have no idea how expensive a request could be (= how much resources it needs), you’re probably not doing a very good job scaling it.

You can usually limit memory usage by processing data in smaller batches of a known size. If you’re loading thousands of rows from the database to process, divvy them up into smaller batches of say 100 rows, process those, then do the next batch. This ensures that you never exhaust your memory once the amount of rows grows too large to fit in there: it’ll never have to hold more than 100 rows at once!

Example

Let’s say we want to retrieve a random row from the database:

BAD

SELECT *

FROM tablename

ORDER BY RAND()

LIMIT 1;

This is mostly a CPU-intensive task: MySQL will iterate all rows and calculate a random number per row. As the amount of rows grows, this operation takes longer to complete. As it takes the machine longer to respond, it will process requests at a slower rate.

Actually, as this grows even larger, MySQL will also no longer be able to keep the random numbers in memory & will save them in a temporary table on your hard disk. This will be much slower to access than data in memory, so that too will at a certain point start affecting the response time drastically.

WORSE

Even worse would be fetching all rows from the database, passing it to your application and calling array_rand or similar on it. This would not scale because of memory: once the size of your table outgrows the available memory, you’ll crash.

BETTER

SELECT @rand := ROUND((RAND() * MAX(id)))

FROM tablename;

SELECT *

FROM tablename

WHERE id >= @rand

LIMIT 1;

Regardless of the amount of rows (5 or 5 billion), We’ll always just get the max id from the database, generate 1 random number lower or equal to that, and get 1 record (which MySQL will easily fetch via the PK index). This scales! No matter how many rows we grow to, this feature will never ever be harder to compute.

Note how I do >= instead of =, and have a LIMIT 1: that’s just to ignore potential gaps in ids. We could generate a random id “32434” that no longer exists in the DB - this query will also settle for 32435 in that case.

Storage

While images & video will often consume plenty of storage, the biggest problem with storage is usually your database. As long as you know what machine you save your images/videos to, you can easily retrieve them.

Most of the top websites deal with so much data that it hardly fits in one database. But distributing the data over multiple servers is easier said than done, as the data is often linked to each other.

As your database grows, you might consider moving some problematic tables to their own dedicated server. Data in multiple tables often needs to be joined against one another, though, which is quite impossible if it’s spread among multiple (physical or virtual) machines.

Sharding

Instead of distributing specific tables over several machines (which causes JOIN issues), you’re often better of finding a common shared column, by which you decide how to distribute your data.

You could have multiple database servers, each of which have the full database schema. But every server will hold different data.

A simple example would be a blogging platform provider where you sign up for a blog hosted on their server(s). Servicing thousands of blogs from one machine may not be feasible, but they can easily distribute the blogs across multiple machines. As long as all the data from my blog is on the same machine, things should be pretty easy. Your blog could perfectly well be on another machine then, its data will never have to be joined with mine.

A more complex example could be a social network. Lots of users, lots of data per user - too much for any one machine. All of the data for my user account (my settings, my images, my messages, my status updates, …) could live on one machine, while yours may be stored on an entirely different machine. In this case, the data is sharded to different servers based on the user id.

We’ll have to be more considerate about how to distribute the data though. When viewing a single person’s status updates, we’re requesting data from only one machine. However, when we want to see a stream of status updates from all of our friends, that could be located on 20 different machines. Not a thing you’d want to do.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves here: sharding your database can be incredibly complex and be a really big deal to implement and maintain. Moore’s law may have machines growing at a faster rate than your needs ever will, so you likely won’t even have to bother with it.

For more technical details about sharding: Jurriaan Persyn wrote an excellent article on how they sharded Netlog’s database.

Database replication

Database replication is about setting up a master database with multiple slaves. The data is then always written to the master database, who in turn replicates it to all the slave databases. All the data can then be read from the slave databases.

If you have an enormous amount of reads, you’ll only need to add more slaves. Your master database then only has to deal with the writes, of which there are hopefully relatively few.

Sharding will likely be the solution for write-heavy applications, replication for read-heavy problems.

Cache

The magic bullet! Well, not really, but it can be incredibly helpful. Caching is storing the result of an expensive operation where it is known that the result will again be the same the next time. Like storing the result of a call to an external API into your database. Or storing the result of some expensive query or computation to memcached.

If you have a CMS & store all pages in the database, there’s no point in getting that navigation from your database on every single page request. It won’t just change at any given time, so you can simply store a static copy of it in cache. Once a new page is added to the navigation, we can just purge/invalidate that cache so that the next time, we’ll be fetching the updated navigation from storage. Which can then again be cached…

Cache can come in many forms: a Memcached or Redis server, disk cache, temporary cache in memory… All that matters is that reading the result from it is faster than executing it again.

Note that introducing caching will increase the complexity of your codebase. Not only do you now have to read & write data from & to multiple places, you also need to make sure they’re in sync and data in your cache gets updated or invalidated when data in your storage changes.

Network

Network requests are usually not really considered but can drastically slow down your application if you don’t carefully limit them. In a production environment, your database server, caching server & whatnot will likely be on another network resource. If you want to read from your database, you will connect to it. Same for your cache server.

Although probably very little, connecting to other servers takes time. Try to make as few database & cache requests as possible. That’s especially important for cache requests, as they are often thought of as very cheap. Your cache server will be very quick to respond, but if you ask for hundreds of cached values, the time spent connecting to the cache server accumulates.

If possible, you could attempt to request your data in bulk. This means fetching multiple cache keys in once. Or fetching all columns from a table at once if you know you’ll be querying for a particular column in function A and another in function B.